Interview: Kelly Hoffer

Last May, Kelly Hoffer, poet, educator, and alum of the Literatures in English PhD program here at Cornell, released her debut collection, Undershore (Lightscatter Press, 2023). I was fortunate to attend her book launch at Buffalo Street Books, where she read to a packed room and shared the cyanotype quilt and textile book that accompany the collection. Vivid, sonic, and sensory, Undershore probes the indelible linkages between mother and child, remapping how relationships continue, even after death. Far from a memorial, Undershore enacts the work of reconstructing a self in the wake of life-altering loss. When I spoke with Kelly in September, we talked about getting out of the poem’s way, the particularities of grief, and conspiring with the dictionary.

Kelly Hoffer is a poet and book artist. Her debut collection of poetry, UNDERSHORE (2023), was selected by Diana Khoi Nguyen as the winner of the Lightscatter Press Prize. Her second manuscript, Fire Series, was a finalist for the 2021 National Poetry Series. Her poems have appeared or are forthcoming in Gulf Coast, TAGVVERK, American Chordata, Denver Quarterly, Chicago Review, and Prelude, among others. She holds an MFA in Poetry from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and a PhD in Literatures in English from Cornell University. She currently teaches in the MFA program at the University of Michigan as the Helen Zell Visiting Professor in Poetry. Learn more at https://www.kellyrosehoffer.com/.

Aishvarya Arora: Thank you for Undershore. I spent the summer with this book—I was reading it while traveling and listening to audio of the poems while driving, which was such a gift to have. While the seasons were changing in Ithaca, the book’s precise admiration for the natural world really attuned me to the landscape here and the particular flowers and end of season blooms.

Kelly Hoffer: That’s great, a flower moment, that’s what we want.

AA: To start off, I wanted to talk about how our senses succeed and fail in the midst of grief. Sensory language is such an important part of this book. In “Visitation [in the dream where],” you write, “sound moves / fastest in solids. faster in water than / in air. breath, it turns / out, is the slowest medium, and the words I / have are thick in their churning over. the materials / only few and so thin.” Wow. That line really framed my experience with the rest of the collection.

Trying to be with someone in their absence requires moving beyond our senses. The collection really enacted that. I enjoyed how your poems dismantled and reconstructed sensory input to defamiliarize imagery. For example, in “Darkness is to Weight As Lightness it to Lightness,” you write, “ a hallway is two windows connected by a tube / or two squares of light surrounded by heavy dark.” Then there is “Cataract,” one of my favorite poems in the collection, which uses the etymology of cataract to map flooding waters onto the failure of light to flood through an eye. Such a visceral way to render our ability to perceive anything as a rather surreal accomplishment.

What is Undershore’s relationship to the sensory? What is your own relationship as a poet to the sensory and bringing that into your work?

KH: When I started writing, my first real love was image. That was the way I moved through the composition process. I would alight on an image that felt hyper-charged and then find a way to jump to another hyper-charged image. The Imagists were a really influential group of poets for baby poet Kelly. I'll also say that I compose by ear a lot. I'm constantly reading out loud to myself and this actually makes it difficult for me to write in public. I'm not someone who usually writes at a coffee shop because I have to compulsively read my poems to myself. So, thinking about that moment in “Visitation [in the dream where],” there's a sense there of the breath…well, this is going to get a little proto-academic.

AA: I'm super here for that.

KH: Post Olson and projective verse, we've really thought about breath as poetry's medium. I buy that and think there's more to it. I think about breath punctuation—the way a line can punctuate breath and how that gets into our bodies when we're reading and composing. Thinking about grief specifically—when you're attending to someone who is at the end of their life, there's a stage for most people, the last couple of days of hospice, when you're probably not talking anymore, and then, at the very end, probably not even conscious. Breath becomes the thing that you're monitoring as a caretaker or onlooker. The body moving and breathing is slightly different from articulation. Poetry coordinates and regulates, but also disturbs the breath. When Olson gets really excited about energy and the body and the vibrant breath—there's also something there about a real sensitivity to the end of life. Which is more probably where I would settle.

I'm really a big believer in Frank O'Hara's “go on your nerve.” Go on your nerve. There's something about the sensory that short circuits thinking or allows you to move past the thinking brain, to where you don’t quite know what's going on in the poem.

AA: Yes, finding something that makes it possible to leave the poem to itself.

KH: Jack Spicer talks about poetry as a kind of radio signal, that you have limited agency, that you have to get out of the poem's way in order for it to happen. That feels really true to my experience. I get out of my own way by connecting with the bodily experience of the poem.

AA: I love to hear that you read aloud when you're composing poems. What are you listening for? Does the composition of your poems on the page, which is guided by breath, serve as instruction to the reader for how to pace their reading?

KH: I'm listening for phrasing and I'm listening for rhythm. I'm trying to be sensitive to the reader or generous to the reader. So much of it comes down to feel. If a phrase is difficult to say, do I want it to be difficult? Do I want it to feel kind of tense and totally overly gnarly or gnarled? Or do I want this to be a more smooth experience?

But one of the dangers of composing by ear is that you convince yourself that you've conveyed what you want on the page when it might actually only be happening in your performance. A helpful thing I’ve done in the past is ask workshop leaders to read my poems out loud to me. It's probably apparent from those recordings that I enjoy reading. Part of the joy for me is performing some of my poetry.

AA: I love that, that balancing act. To me repetition is also something that is so based “in ear.” You employ repetition and doubling in numerous ways throughout the collection, which takes place entirely after the passing of your mother.

In “Visitation [in the dream where]”, you write, “so as not to lose you, the hospital / lists your name with your mother’s on your / baby wristlet.” Towards the end of the collection, in “Gladiolus Stem”, this image gets troubled: “the lover I have will never know my mother. the / child I don’t have will never know my mother…if you lose the baby late enough, / your milk still comes in, and no one to eat it. I’m / confusing bodies. it’s my mother I’ve lost, not / my baby. my lover I am waiting to lose.” I thought that was so moving and funny.

To me, these lines speak to two-ness, being in a dyad, and the collection's larger effort to negotiate what it means when one person in that unit is lost—how to remap that relationship. I found your poems often enacted this two-ness on the level of the line, through the doubling of language, making the feeling of being in a pair, and an incomplete pair, palpable in numerous ways throughout the collection.

Could you speak more to your approach to repetition in your work? Doubling and doubling that has gone askew?

KH: Your question is really perceptive. It's definitely true that this book was written in the wake of my mom's death. I was thinking through what her death meant for my identity—the way I relate to people, period, not just my mother. The “Visitation” series was generated by dreams I was having about my mother after her death. In those dreams, I sometimes didn’t know she was dead. We would talk about things, and at times she would be upset with me. There was a whole range, some of those dreams were nurturing and some less so. Still, I was grateful for these dreams because it meant that my mom was continuing to have a life of her own, that she could surprise me, that she wasn't becoming calcified in my memory. She was an active entity that was changing and evolving. This is just to say, that even when you lose a part of that dyad, that dyad continues.

I also think about dream space as a mirrored doubling of waking space. The title of the book came from thinking about landscapes on the periphery of dream and waking, between the two spaces. At the bottom of the ocean, there are hyper-salinated underwater lakes. The title, Undershore, came from me imagining being on a shore of one of these lakes under the ocean. These “undershores” also became a potential physical manifestation of where some of these visitations were happening, that space as a doubling of my waking life.

When I first wrote some of these poems, I got feedback from readers that I respect and trust and love, who observed that I had all these grief-driven poems and then I had some erotic, sex-driven poems. My readers were uncomfortable about how porous the line between those two things was. This is also what your question hints that—do all of our dyadic relations end up repeating each other? For me, that possibility is one of the generating concerns and tensions of the book—how an erotic connection, a connection with a lover, cannot be wholly disentangled from other kinds of familial relation, and specifically, a strongly embodied caretaking relation. I understood my readers’ discomfort, but it’s just the way it was for me.

AA: Grief is that way. I’ve been researching the neuroscience of grief, and learned that grief is a motivational state, just like desire. It's a grasping for, or reaching. I don’t even want to say they’re two sides of the same coin, because they feel so together.

KH: That's resonant with so much of my thinking. One of the things about grief is that there will be new people in your life that the departed person won’t know about. My current partner, who I've been with now for seven years, I met him after my mom died. They're never going to meet each other. That's really strange for me because they are both giant influences in my psyche, in the way that I relate to the world, and the way that I attach. Another way to think about some of these poems is that I’m creating a space where some of those meetings can happen, even if they're only happening through language and not theatrically.

AA: I’d love to hear about the various poem series in the collection, including the 8 “Visitation” poems and poems that excavated the definitions of words, specifically, “Cataract,” “Worry,” “Pile,” and “List.” How did these poem series develop in your compositional process? Further, how did they impact your sequencing of the collection?

KH: I'm endlessly fascinated by technical diction. I love specialty language. I love the particularities, and I’m obsessed with idioms. I'm fascinated by the polyvocality within a word, how certain words have multiple definitions.

The dictionary poems often started when I would discover a secondary definition of a word that was new to me. For example the poem “List” began when I learned that “to list” can also mean “to desire.” I went to the Oxford English Dictionary (OED), which collects instances of antiquated definitions, so you can see the way a word has evolved over time. I’ll add the disclaimer here that it is a hegemonic mapping, and the OED absolutely consolidates linguistic power, but it’s still an incredibly generative tool for me.

When I saw various definitions of “list,” I got so excited and decided to use each sub-definition as a prompt for a section of the poem. It was important to me that I didn't use the first definition. For me, this gets back to this question of how do you get out of the poem's way? In my experience that happens when I have a form that I'm working with as a generating mechanism. There have been times when, for example, I've written in syllabics. There are a couple of poems in the book that are in syllabics. That was a way for my intellectual brain to be doing something and to let my image-nerve brain do something else. Working with the dictionary gives me similar constraints, which means similar freedoms—it allows me to get associative. I also love the idea that the dictionary is working against itself. And I love the idea that the poem is potentially adding some disturbance to the dictionary. The OED is not just an inspiration for the poem, the poem is intervening in the OED, I hope.

I’m not the first poet to explore this terrain. I’m thinking of Harryette Mullen’s Sleeping with the Dictionary—she's a huge figure for me sonically as well—I feel so much kinship with her poetics. I just taught the other day in one of my courses, Lyn Hejinian's The Rejection of Closure, an essay in which she talks about her experience of navigating the dictionary, how she looks up one word, which will refer her to a different word. “Mammary” refers her to something like “nipple,” but then “nipple” doesn't refer her back to “mammary.” She talks about this as a very illustrative, true example of the way that there are real connections within language, but also there's a kind of wandering or entropy that language can’t escape.

That's also my experience of hanging out with the dictionary—even though it's this theoretically organized structure, there's also so much space for different kinds of subversion.

AA: I love the idea of words endlessly departing from each other. That's so much of why this book unsettled my relationship to certain words. While giving all these definitions and sub definitions, it's actually emptying them out and making its own departures. The other piece I think about with poem suites is how they exist within a collection. How did you sequence Undershore?

KH: Pretty early in the process, I knew that I wanted to have these “Visitation” poems coming at intervals because I wanted it to mirror the way that my experience of grief has been periodic. I'll have moments where it does not feel like a super present part of my daily life. Then I'll have one of these dreams, or I'll have a specific sensory reminder, and all of a sudden it's super present. I wanted to recreate that in the pacing of the book.

The book as its sequenced is pretty close to the way that it was when I submitted it to the contest. Both my editor and I landed on a metaphor of threading, there being sort of multiple threads or areas of concern that bleed into one another, but also interweave throughout the collection. With this model of weaving together formally diverse sets of poems, it’s important to think about how to set your reader up to understand the various kinds of poems in the book pretty early. One of the things that my editor and I worked a fair amount on was thinking about the best way to sequence the opening poems so they teach you how to read the book.

AA: There is so much generosity in Undershore. As readers, we get to see the concerns of the collection refract through numerous mediums—cyanotypes, audio recordings of you reading the poems, and the textile book made by Lauren Callis. I also know you’re a book artist in addition to being a poet. I would love to hear more about the process of re/creating Undershore as a cyanotype quilt. Why did you choose cyanotype? Do you have a favorite panel? How would your dream reader engage with the multiple forms that Undershore exists in?

KH: First of all, I should really say that the generosity is one that I was invited to by my press, Lightscatter Press. They are a multimodal poetry publisher. As a part of their mission, they work to create multiple routes or multiple pathways into every book they publish, that is, multiple ways of experiencing the book.

When I submitted my manuscript, I did not know what that multimodality was going to look like. I'll even admit that I was a little nervous about it. I really wanted the poems to stand on their own and I did not want them to feel like they needed this multimodal presentation to land or be appreciated. It was important to me from the beginning that the poems did not get overshadowed.

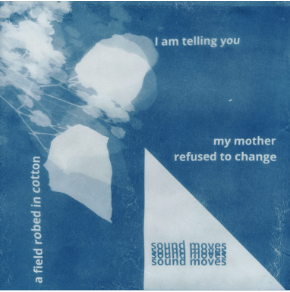

My publisher Lisa Bickmore is just incredible and has such an openness and willingness to pursue ideas with her authors. She noticed the volume of fiber related diction and imagery is in the manuscript, and she suggested one fruitful way to think about the book was as a textile with recurring threads. We followed that line of thinking for a while before arriving at the idea of a digital quilt. Quilts are modular forms, and in a digital version, you can move squares around and provide an alternate sequencing for the poems.

I knew pretty early on that I wanted the cover image to be a cyanotype of a piece of sea kelp by the photographer Anna Atkins from the 1850s. There's a whole history of using cyanotypes for botanical cataloging. That Atkins piece is from one of her botanical catalogs of British algae. I was so excited by the image, and so cyanotypes became an obvious and appealing medium. Cyanotyping is a solar-printing process that’s low cost and user-friendly. You don't need a dark room; you can make the prints anywhere with a sunny space and a bathtub.

Each square in the quilt corresponds with a poem in the book and each of the squares has text. I got the text onto the squares by designing a text layout in Photoshop, laser printing a negative, laying this negative on top of the photosensitized material, and then exposing it to light. The process also allows you to work in layers. I love being able to play with multiple exposures, which also gets back to your question about repetition and being in touch with your senses. It's super time oriented, super fast.

A lot of these exposures are happening in 30-second intervals. Making so many fast exposures was both very exciting and a ton of work, but in the end it was an exceptionally generative process. Like a lot of first books, this book was written over many years. There are poems in the book that are eight or more years old, and when I go through the manuscript now, some poems feel like they were written by a totally different person. One magical thing that happened in the process of making this quilt was that I was able to re-engage those older poems. They became alive for me again, especially since I was taking pieces of language from the poems and creating a broadside of those fragments. For example, in “Visitation [in the dream where]” there is a line that goes, “my name / is the last name my mother refused / to change.” In the quilt square I've changed the lineation. I fragmented it and a whole different sentiment that's nested in the original poem is given emphasis and breath in the quilt.

There are also technical accidents that worked out beautifully. For example, the square that corresponds to “Cataract,” I printed on a cloudy day and the light is more diffuse and the shadows less exact. It’s almost as if the square is being viewed through a cataract because of the blurring.

AA: Are there new things you've come to understand about the book through its release, through its touring?

KH: This book and its making felt highly personal, almost idiosyncratic. There was some anxiety on my part that when it was released, it would not necessarily reach people, or if it did reach them, then it would not communicate. Grief is a common experience, but it's so particular. Even among my siblings—I'm one of four—we've all had our own ways of being devastated by the loss of our mother. The ways that we've processed it and wanted to talk about it (or not talk about it) and move through it have been so different, so totally different. I'm sensitive to grief being highly individual, and I didn’t want my expression of grief to speak over anyone else’s.

Because of this, some of the most meaningful comments and reactions to the book have come from other people who have experienced substantial, life-altering loss. After reading the book, several people that I had known for years reached out and shared with me that they had also lost a parent. Hearing that the book was meaningful for them has been the greatest gift. We can get protective of our grief, I’d never want to intrude on that sacred, private space. I want a reader to be able to succumb to the poems and find something in them without feeling pushed into an emotional experience that feels overly coordinated. I want to respect the particularity of everybody's loss. And the fact that this book was able to create a kind of community of grief without disrespecting that particularity has been just the most meaningful and wonderful surprise.